Guide: Living Together or Living Apart

Guide: Living Together or Living ApartIf you’re in immediate danger, call:

911, police if you’re in immediate danger or if you’ve been hurt. If your area doesn’t have a 911 service, call your local police emergency number or the RCMP. If you don’t speak English, ask 911 for an interpreter.

1-800-563-0808, VictimLinkBC (24 hours a day, 7 days a week) for support services in many languages and to find a transition house. Transition houses, sometimes called safe houses or shelters, are places where you can go if you’re in danger. Transition houses offer their services for free.

211 to get information from BC211 about support services in your community. BC211 is available province-wide.

Once you’re safe

Talk to a lawyer. You might want to get a protection order if you’re afraid for your safety or your children’s safety and want to keep your partner away. If you can’t pay for a lawyer, you might qualify for a legal aid lawyer to take your case. When you apply, tell Legal Aid BC, say you’re leaving an abusive partner.

See Help from a lawyer for how to contact Legal Aid BC to apply for legal aid.

Get free help from family duty counsel. If you don’t qualify for your own legal aid lawyer, you might get some help from family duty counsel. Duty counsel are lawyers who provide limited free help to people with low incomes who have family law problems. Duty counsel give you legal advice or speak on your behalf in court on simple matters. But, they can’t take on your whole case or represent you at a trial.

See Help from a lawyer for contact information.

Get free legal information. Read Legal Aid BC’s free online family law resources.

See the Family Law in BC website. This website has step-by-step guides to legal processes, information pages, illustrated stories, videos, and other ways to help you learn about and settle family law issues, including:

- separation and divorce,

- guardianship,

- decision-making responsibility and parenting time,

- parenting arrangements and contact, and

- child support and spousal support.

This resource explains the basics of family law in BC. It includes information about:

- types of relationships,

- what to do if you decide to separate,

- how to work out agreements before you live together, while you live together, or after you separate,

- how to work out parenting arrangements and child support if you have children,

- how to sort out other money matters,

- what happens if you go to court,

- how to get a divorce,

- specific concerns if you’re a newcomer (immigrant) to Canada, and

- where to get legal help.

The information applies to non-Indigenous families and Indigenous families in BC.

Family law can be complicated. But with the right information and help, you can solve many issues on your own without going to court. This resource explains your options and where you can go for help.

Finding out your options is a positive first step. Many free and low-cost legal services are listed at the end of this booklet to help you decide what to do.

Indigenous peoples

This resource uses the word Indigenous, which includes Status and non-Status Indians, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people.

What you need to know

Types of Relationships

Types of RelationshipsCommon-law relationship is the term many people use to describe unmarried couples who live together for a certain period of time in a marriage-like relationship. But it’s not a term used in the BC Family Law Act or the federal Divorce Act. These laws just call them spouses.

Who a spouse is

Under BC law, you’re a spouse if you:

- marry another person, or

- live with someone in a marriage-like relationship for at least two years, or

- have lived with someone for less than two years and have a child together. In this case, though, you aren’t considered a spouse when it comes to division of property, debt, or pensions.

This means couples who have lived together for more than two years have the same rights and responsibilities as married couples. Spouses can be in same-sex or opposite-sex relationships.

| Married spouse |

|

You are a married spouse if you had a legal marriage ceremony (religious or civil). You stay married until one spouse dies or applies in BC Supreme Court for a divorce or annulment to legally end the marriage. |

| Unmarried spouse | |

|

If you lived together in a marriage-like relationship for two years or more |

If you lived in a common-law relationship for less than two years and have a child together |

|

BC family law says you and your partner are spouses in all areas of family law, including spousal support and dividing property, debt, and pensions. Many people call this a common-law or unmarried spousal relationship. In this resource, we’ll call this a common-law relationship or living common-law. |

BC family law says you and your partner are spouses in the areas of parenting, child support, and spousal support, but not when it comes to dividing property, debt, or pensions. Laws about parenting arrangements and child support apply to all parents no matter what their living arrangements have been. |

| More about spouses |

|

Which laws apply

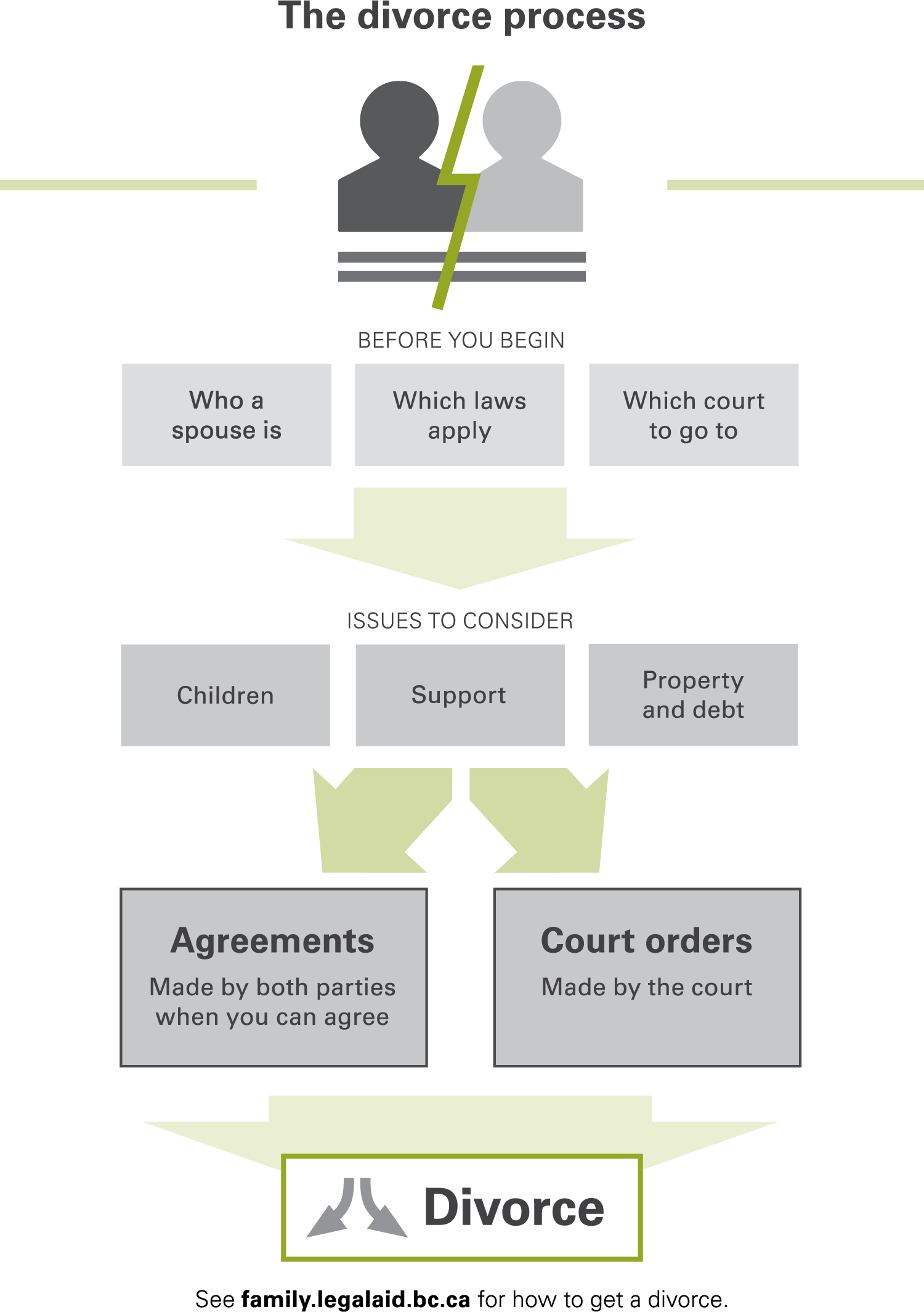

The two laws you need to know about are the BC Family Law Act and the federal Divorce Act.

| BC Family Law Act | Divorce Act |

|

Applies if you’re |

Applies only if you’re |

The two courts in BC that can make court orders about family law matters are the BC Provincial Court and Supreme Court.

See the chart Which court to go to that explains which court you go to if you want a judge to make an order about a family law issue.

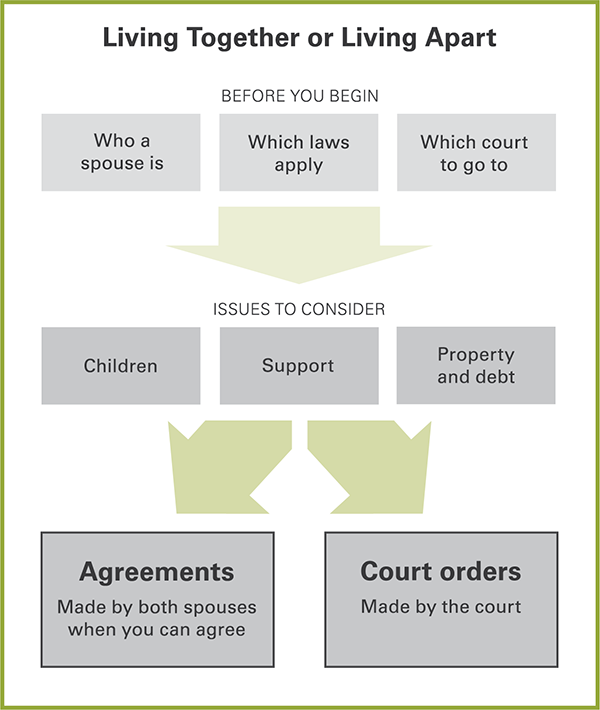

Living Together — Making Agreements

Living Together — Making AgreementsSometimes you can prevent conflict about your property, savings, and debts if your relationship breaks up by making a written agreement with your spouse. These are usually called cohabitation, marriage, or prenuptial agreements. You can make them before or while you live together, just in case you break up.

When can you make an agreement?

You can make an agreement:

- before you start to live together or get married,

- any time while you live together or during your marriage, and

- after you separate. This agreement is usually called a separation agreement.

An agreement is legally binding when you sign it, so it’s important to consider whether you need one. It’s a good idea to get legal advice about your situation if you can before you sign an agreement.

See Living Apart - Separation for more about separation agreements

Do you need an agreement while you live together?

Before deciding whether you need a written agreement while you live together, consider what the law says and whether you want to agree to something different. It’s really important to get legal advice.

The Family Law Act supports the idea of an economic partnership and recognizes different roles and contributions of partners, including non-financial contributions, if people separate. Many people don’t write an agreement while they live together and are comfortable with this law applying to their situation if they separate.

The law tries to balance supporting healthy relationships by recognizing economic partnerships and obligations to each other, while recognizing what you each brought into the relationship. Make sure you’re clear about what property each of you brought into your relationship.

If you don’t own much or don’t have any large debts, you might not need an agreement.

It might be helpful to have an agreement while you live together if:

- One of you has a lot more assets or debts than the other. For example, if one of you owns property or has a large amount of savings, got an inheritance, or has a huge student loan.

- You’re older and close to retirement.

- You have significantly different incomes.

- You have children from another relationship (including adult children who you want to provide for in the future).

It’s important to remember that an agreement you make while living together can’t restrict any future support arrangements. Also, an agreement could be set aside (cancelled) by the court if it’s found to be unfair.

Sharing information before making an agreement

Before you make an agreement, you and your spouse must share all the important information you need to make a fair agreement. This includes financial information about your income, expenses, assets, and debts available in your income tax returns, bank statements, and other financial documents. The law says you must give your spouse “full and true information” to resolve a family law dispute. This applies to any agreement you make while you’re living together and family law agreements you make after you separate. If you hold back information, a court can take various steps, including setting aside (cancelling) your agreement, ordering you to provide the missing information and documents, or ordering you to pay a fine or the other person’s legal costs.

What an agreement can cover

Your cohabitation, prenuptial, or marriage agreement can be about what happens while you live together and what happens if you separate. However, you can only make agreements about your children after you separate. The courts will not accept an agreement that limits spousal support or child support.

Dividing family property, assets, and debts

It can be hard to talk about finances, and money is often a huge source of conflict in relationships. It’s important to have conversations about your shared values.

It’s helpful to be clear about the financial value of what you each brought into the relationship, and what debt each of you had. This makes it easier to divide family property fairly if you separate.

One way to do this is to take a “snapshot” of each person’s finances when you start to live together. You can do this by taking photos of current bank statements or by making a dated record of the amounts of savings, the amount owing on loans, the value of any investments, and the value of any property, like a home or apartment that one of you might own. It’s helpful to do this whether or not you decide to make an agreement.

You can decide together:

- who brought what into the relationship.

- how you’ll share household expenses.

- whether you’ll have separate or joint bank accounts and credit cards.

- how you’ll share any new debt you take on together under both your names.

- who’s responsible for debts either of you take on under your own name before or during your relationship.

Before you sign an agreement

Signed agreements are legally binding. It’s a good idea for both you and your spouse to see a lawyer to make sure your agreement is fair and meets legal requirements before you sign it. It’s especially important to see a lawyer if you or your spouse has a pension plan. It’s complicated to calculate the value of a pension, because even a low-paying job can have a large pension if a spouse has had the job for many years.

How to make an agreement before or while you live together

| Find out your rights and responsibilities See the Family Law in BC website for where to get legal advice. |

| Make a list of the topics What topics do you need to agree on? Consider things like the property and debt each of you brings to the relationship, how you’ll share household expenses, and spousal support |

| Share financial information This includes tax returns, pension statements, bank statements, and information about debts. |

| Write out the agreement You, a lawyer, or a mediator can type it and print two copies. (To find a mediator or lawyer, see Help to make an agreement.) |

| Review the agreement Each of you should have a lawyer review your agreement and give you legal advice before you sign it. |

| Sign the agreement If you’re sure that the agreement is fair and meets legal requirements. Don’t sign if you feel pressured. |

| You each need to sign two agreements so that you each have an original signed agreement. The witness doesn’t have to be a lawyer. You and your witness can initial and sign two copies in front of each other. Send them both to the other person, who sends one signed and witnessed version back to you. |

|

|

| If your situation changes It’s difficult to change an agreement after you sign it. It’s a good idea to build in a future review, because, for example, you might have children together, your children’s needs and interests might change, or your financial circumstances and incomes might be different. |

Living Apart — Separation

Living Apart — SeparationThere’s no such thing as a “legal separation.”

How to separate

Whether you’re married or living with someone in a common-law relationship, you become separated as soon as one (or both) of you:

- decides to separate,

- clearly tells the other spouse the relationship is over, and

- acts like it’s over.

Typically, spouses are separated when they live apart. But, you can live in the same house and still be separated. You don’t have to move out. But you do have to stop living in a spousal relationship; for example, you stop sharing the same bedroom, stop sharing meals, stop going out together as a couple, and so on.

- You don’t have to see a lawyer, go to court, or sign a document to be separated.

- You don’t need your spouse’s permission to separate; it’s enough for you alone to decide the relationship is over.

If you’re married, you’re legally married until you get a BC Supreme Court order for divorce (or annulment, if applicable). You don’t need your spouse’s permission or agreement to apply for a divorce.

If you’re unmarried, you don’t need to get a divorce. Your spousal relationship is over as soon as you separate.

How to avoid going to court

It can be less expensive, less stressful, and faster to settle your family law issues without going to court, if you can. See How to reach a separation agreement below for some options to resolve your disagreements without going to court.

Both the Family Law Act and the Divorce Act recommend that you try to resolve any disputes outside of court first, and go to court only if you can’t come to an agreement another way.

You might not have to go to court if you can agree on your family law issues, including the following:

- parenting arrangements,

- child support and spousal support, and

- property and debt division.

If you and your spouse can make an agreement, you’ll save time, money, and emotional turmoil. The process will be private, and you’ll also be able to keep control of important decisions that affect your family.

It’s important to talk to a lawyer before you sign an agreement. It can be a long and difficult process to change an agreement (especially about property division or spousal support) after you sign it.

An agreement after separating

You can make an agreement after you separate (called a separation agreement). If you made a prenuptial or marriage agreement, you can refer to it in the separation agreement and attach it as an exhibit. If you can’t agree on all the issues, you can make an agreement about some of the issues and ask a mediator or other dispute resolution professional to help you settle the rest. You could also ask the court to make a court order if you’re not able to reach an agreement.

See How to make a separation agreement

How to reach an agreement when your relationship ends #

|

Find out your rights and responsibilities |

|

Make a list of the topics |

|

Share financial information |

|

See if you can agree |

|

Write out the agreement |

|

Review the agreement |

|

Sign the agreement |

|

You each need to sign two agreements, so you each have an original signed agreement. You must also have your agreement witnessed, especially if it deals with property. The witness doesn’t have to be a lawyer. You and your witness can initial and sign two copies in front of each other. Send them both to the other person, who sends one signed and witnessed version back to you. |

|

|

|

If your situation changes |

|

To have your agreement enforced after you separate |

Parenting arrangements

When you separate, it’s helpful to make parenting arrangements that set out how you and the other parent will divide parenting time and make daily decisions that affect your children. It’s also helpful to decide how you and the other parent will make significant decisions, for example, about education, health care, and religion. (The BC Family Law Act calls this parental responsibilities. The federal Divorce Act calls it decision-making responsibility.)

Any agreement about children must be in their best interests. It’s important to take the children’s opinions and feelings into account, if they can express them. Your agreement might need to change as your children grow and develop and your circumstances change.

You can start preparing an agreement about children, support, and property right away. Or you can take your time with it. Note that you can only complete an agreement about children and support once you’ve separated.

If you don’t have a formal agreement

After you separate, you don’t need to have a formal agreement about your parenting arrangements. You and your spouse might develop informal routines for your children and make parenting decisions. Even if you don’t have a formal agreement, it’s best to check with the other parent before you change the routine.

How to reach a separation agreement

You might be able to reach an agreement with your spouse by working with them directly.

Or, you might need help to work through the difficult issues that come up after you separate. Here are some options for where to get help to reach an agreement.

Mediation

A mediator can help you and your spouse work together to identify and resolve the family issues caused by your separation or divorce.

Mediators don’t take sides, make decisions, or force solutions on you. They encourage you and your spouse to listen to each other and help you communicate and find ways to solve your issues. Mediation can help you find solutions you can both accept. If you have children, the mediator helps you reach an agreement that’s in the best interests of your children.

See Help to make an agreement for where to find a mediator.

Family justice counsellors

Family justice counsellors are specially trained government employees at Family Justice Centres across BC. They also work at the Justice Access Centres in Abbotsford, Nanaimo, Surrey, Vancouver, and Victoria. They can provide services in person or virtually (by phone or videoconference).

Family justice counsellors provide free services for parents and family members, and can:

- give you legal information and help you explore ways to settle parenting and support issues,

- give you legal information about how to get or change family agreements or orders,

- provide free mediation services, and

- provide initial counselling and refer you to other services.

See Help to make an agreement for where to find a family justice counsellor.

Family lawyers

Lawyers who specialize in family law can help you reach a fair and lasting agreement. Some lawyers offer lower-cost legal services including:

- independent legal advice on agreements. Brief advice on an agreement you’ve already drafted.

- unbundled or limited scope services. Instead of representing you from start to finish, they do only specific tasks and you do the rest; for example, you might hire a lawyer to deal with your property division issues, not your parenting issues (which you might be able to get help with from a family justice counsellor).

- sliding scale. Hourly rates that depend on what you can afford to pay.

- flat rate. Doing specific tasks for a set fee.

- legal coaching. Giving you legal advice while you negotiate and develop a family law agreement.

See Help from a lawyer for where to find a lawyer.

Collaborative family law

Lawyers who practise collaborative family law work together with you and your spouse to find solutions that work for both of you. You and your spouse each still have your own lawyer. The collaborative family law process is different from a traditional separation or divorce in a few important ways:

- No court. You, your spouse, and your lawyers sign a written agreement

that says you’ll work together to solve your issues without going to court.

If you end up going to court, you have to find different lawyers to represent

you in court. - Honest communication. You and your spouse agree, in writing, to open and

honest communication. This includes openly sharing information with each

another; for example, about your finances. - Team approach. You and your lawyers work as a team to solve your disputes,

whether the issues are about support, dividing property, or parenting your

children. The team can also include other members, such as specially trained

lawyers, divorce coaches, child specialists, and financial advisors, as needed. - Four-way meetings. Instead of your lawyers doing all the talking, you, your

spouse, and your lawyers have a series of meetings. Sometimes your lawyers might meet alone to decide what the meetings will cover. Or they might share information about you or your spouse to help solve the issues. The number of meetings depends on how many issues you and your spouse face and how complex they are.

Collaborative family law involves hiring lawyers and other professionals, and it can be expensive. It’s important to understand what you can afford and are prepared to pay.

See Help to make an agreement for how to find a collaborative family lawyer.

Arbitration

An arbitration is an out-of-court process in which you and your spouse hire a neutral, trained person (called an arbitrator) to make a decision resolving your family law problem. The arbitrator acts like a judge, listening to both of you and then making a decision that is legally binding.

See Help to make an agreement for how to find an arbitrator.

Parenting coordinators

A parenting coordinator can try to help you and the other parent resolve disagreements about your parenting arrangements set out in a separation agreement or court order. If you can’t agree, then a parenting coordinator can make a binding decision that you must both follow.

You can agree to get a parenting coordinator yourselves, or a judge can order you to see a parenting coordinator if they feel you need one.

See Help to make an agreement for how to find a parenting coordinator.

How to make your agreement legally binding

No matter how you make your agreement, take time to think about it and have a lawyer look at it before you sign it. You and your spouse each need to have different lawyers review the agreement. Lawyers aren’t allowed to act for both parties in a family law matter.

Each of you must sign the agreement. If your agreement is about property or spousal support, at least one other person must witness your signatures. The same person can witness both signatures. Don’t sign an agreement if you feel pressured.

Generally, a signed agreement is legally binding. But the court won’t enforce an agreement (order you and your spouse to follow the agreement) that isn’t in the best interests of your children.

How to enforce your agreement

You don’t have to file your signed agreement at a court registry or online. However, as long as it includes parenting, support, or both, you can choose to file the agreement at a court registry (in person or online). Once your agreement is filed, the court can enforce it, particularly if it’s in the best interests of your children.

You can also enroll your filed agreement with the BC Family Maintenance Agency (BCFMA), previously known as the Family Maintenance Enforcement Program (FMEP). This program enforces the child support and spousal support parts of your agreement.

How to change or cancel an agreement

If you and your spouse agree, you can change your agreement without going to court. You just need to write and sign a new agreement and have it witnessed. Be sure that the new agreement makes it clear what’s changing and what’s not. Have the new agreement reviewed by a lawyer before you sign it.

If you and your spouse can’t agree, you can get help from a dispute resolution professional such as a mediator to help you come up with a new agreement. (See the options listed in How to reach a separation agreement.) Or you can apply to the court to change all or part of an agreement and replace it with court orders. The court follows the Family Law Act to decide whether to change all or part of an agreement.

Whether the court changes the agreement, and for what reasons, depends on the issue. For example, the court might change an agreement about parenting time only if the agreement isn’t in the best interests of the child.

See Best interests of the child.

It’s sometimes difficult to change agreements about financial issues. It’s a good idea to see a lawyer before agreeing to property division or spousal support.

The chart When a court sets aside or replaces an agreement which explains when the court can set aside (cancel) or replace an agreement.

If you plan to leave the home you share with your spouse

Here are some important things to take with you:

- financial information, such as:

- your tax returns for at least three years

- bank account, credit card, investment, and debt statements

- copies of recent pay stubs

- BC Services Card/CareCard

- marriage certificate

- passport and immigration documents

- driver’s licence, insurance, and ICBC documents if you take a car with you

- Secure Certificate of Indian Status (secure status card) or Certificate of Indian Status (status card)

- clothing and personal belongings

- medications and prescriptions

- photocopies of information about income and assets you and your spouse have jointly, or your spouse has separately, such as:

- pay stubs

- tax returns

- company records and ledgers

- bank accounts

- investments

- RRSPs

If the children are coming with you, also take their:

- passports

- birth certificates and BC Services Cards/CareCards

- clothing and personal belongings

- medications

Also, write down your spouse’s Social Insurance Number (SIN), BC Services Card/CareCard number, passport number, and date of birth. These can be useful later if you disagree about money and property, or if you need to find your spouse.

If You Have Children

If You Have ChildrenIf you and your spouse (married or unmarried) have dependent children (usually under age 19), you have to make arrangements to take care of them when you separate.

There are two laws that deal with parenting after separation: the BC Family Law Act and the federal Divorce Act. They use similar terms, which can be confusing. Here’s an introduction to the language each act uses.

BC Family Law Act terms about parenting

BC Family Law Act terms about parentingThe BC Family Law Act applies to all parents. It uses the following terms:

- guardianship

- parental responsibilities

- parenting time

- contact with a child

The Family Law Act emphasizes that it’s in the best interests of children to continue relationships with both parents if possible.

Guardianship

Guardians are generally allowed to make decisions about a child. Not all parents are guardians, and not all guardians are parents.

- If both parents have lived together with the child, both parents are generally guardians.

- If a parent has never lived with the child, but they regularly cared for the child, they’re generally a guardian.

- If a parent isn’t a guardian, they can become a guardian by making a written agreement with the other guardian or getting a court order.

- If one parent wants the other parent to stop being a guardian when they separate, they have to agree or get a court order.

- If you’re asked to give up your guardianship, talk to a lawyer. Once you give up your guardianship, it can be a long process to get it back.

- Non-parents, such as grandparents, aunts, and uncles, can’t become guardians through a written agreement. They must apply in court.

Other guardianship issues for Indigenous parents and guardians

If anyone applies for guardianship of a Nisga’a child or a child of another treaty First Nation, they must give notice to the Nisga’a Lisims government or the child’s Nation. The Nation can then take part in the court proceedings.

If you’re a child’s guardian and you live on reserve, your child can live in the band home with you even if you and your child aren’t band members.

If you aren’t sure about something relating to guardianship, talk to a lawyer.

See Help from a lawyer.

Parenting arrangements

Parental responsibilities and parenting time together are known as parenting arrangements. They must be in the best interests of the children.

Parental responsibilities

Parental responsibilities are the day-to-day decisions and important decisions guardians make about a child, such as their health care, daily care, home life, and schooling. Only guardians can have parental responsibilities and parenting time with a child.

Guardians can agree to divide or share parental responsibilities in whatever way works best for the child. If they can’t agree, a court can make an order.

Parenting time

Parenting time is the time each guardian spends with the child.

- During parenting time, the guardian the child is with makes day-to-day decisions and supervises the child.

- Guardians can share parenting time equally, or one guardian can have the child most of the time. They can arrange parenting time in any way that’s in the best interests of the child.

If the child is Indigenous and resides on reserve, it’s a good idea to include some pick up and drop off locations that are outside the reserve in your agreement or order. This way you won’t have to go back to court later to change the arrangements if you, another guardian, or a person with contact isn’t allowed to come onto reserve lands.

Contact with a child

Contact is the time that a non-guardian spends with the child (including a parent who isn’t a guardian).

- Grandparents, aunts and uncles, step-parents, and other people who might be important to your child can apply to court to have contact with a child. A parent or step-parent who isn’t a spouse can also apply for a contact order.

- People with contact don’t have a right to make decisions about a child.

Divorce Act terms about parenting

Divorce Act terms about parentingThe federal Divorce Act applies to parents who are (or used to be) married to each other. The Divorce Act calls them spouses. (Although we still call them parents in this section, you’ll likely see the term spouse used in your legal documents.)

In March 2021, the Divorce Act changed to use words similar to those in the BC Family Law Act to talk about parenting after separation, including:

- decision-making responsibilities

- parenting time

- contact

The Divorce Act also emphasizes that decisions must be in the best interests of the children.

Decision-making responsibility

The responsibility for making important decisions and getting information about a child’s:

- health care,

- education,

- culture,

- language,

- religion and spirituality, and

- significant extracurricular activities.

Parents can agree to divide or share these responsibilities in whatever way works best for the child. If they can’t agree, the court can make an order.

Parenting time

This is the time each parent spends with the child.

- During parenting time, the parent who the child is with makes day-to-day decisions (like bedtime and meals) and supervises the child. They can also get information from others (like teachers and health care providers) about their child’s well-being.

- Parents can share parenting time equally, or one parent can have the child most of the time. They can arrange parenting time in any way that’s in the best interests of the child.

Parents who aren’t or weren’t married, or any person who stands or intends to stand in the place of a parent, can apply for a parenting order under the Divorce Act. They must first apply for permission to do so, in BC Supreme Court.

Contact

The time that someone who isn’t a married or formerly married parent spends with the child.

- Grandparents, aunts and uncles, step-parents, and other people who might be important to your child can apply to court to get contact. They must first get the court’s permission to apply.

- People with contact don’t have a right to make decisions about a child. Nor can they get information about the child’s well-being.

Parents’ responsibilities and children’s rights

Parents are legally responsible for supporting their children until they’re at least 19, and after they turn 19 if they’re still financially dependent.

- Even if you never lived with your child or your child’s other parent, you still have a legal responsibility to contribute to your child’s support.

- If there’s any dispute or uncertainty about whether someone is a parent, the court can order a parentage test.

- Child support is the child’s legal right.

Adoptive parents

Married couples, couples who live together in a common-law relationship, and single people can apply to adopt a child. You can adopt your spouse’s child from another relationship if the child’s other parent agrees. If the child is 12 or older, they must also agree to being adopted.

If adoptive parents separate, they have the same responsibilities and rights as biological parents to make decisions about their child, parenting time, and child support.

Step-parents

Under the BC Family Law Act, you’re a step-parent if:

- you and the child’s parent are or were married, or lived common-law for at least two years, and

- you lived with the child’s parent and the child during the child’s life.

Under BC family law, a step-parent doesn’t automatically become a child’s guardian. You must apply for guardianship of your step-child. But, even if you’re not a guardian, you might have to pay child support for a step-child after you separate.

As a step-parent, you have to pay child support after separation if:

- you contributed to the child’s support for at least one year; and

- a child support application is made within a year of the last time you contributed to the child’s support.

A step-parent’s responsibility to pay child support comes after the child’s parents’ or other guardians’ responsibility.

When deciding if a step-parent should pay child support, courts look at various factors, including:

- the child’s standard of living when they lived with the step-parent, and

- how long they lived together.

Parenting apart

Parenting apartWhen parents separate, they need to figure out how to co-parent their dependent children (usually those under age 19).

This involves working out:

- how you make decisions about the children,

- where the children are going to live, and

- how much time the children spend with each parent.

It’s a good idea to put these parenting arrangements into a written agreement (under the Family Law Act) or parenting plan (under the Divorce Act).

Child protection

Child protectionYou can get free legal help if you or the other parent are being investigated for a child protection matter. If a social worker from the ministry or a delegated Aboriginal agency contacts you to ask questions about your family, call Legal Aid BC immediately to see if you qualify for a free lawyer.

Depending on where you live, you may be able to get help from a lawyer and advocate at a Parents Legal Centre. Legal Aid BC provides this service to help parents who are dealing with child protection issues. The service is available any time after the ministry or a delegated Aboriginal agency contacts you.

Call Parents Legal Centre at 1-888-522-2752 (1-888-LABC-PLC) to find out if there’s a location near you and if you qualify for help.

The law in BC says Indigenous cultural ties are very important for Indigenous children. The child protection process recognizes an Indigenous child’s right to their cultural identity and connection to their Indigenous communities when planning for their care. The child protection process is evolving with the BC government’s recognition and support of the rights of Indigenous communities to make laws and provide their own child and family services.

See An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children, youth, and families for the Best Interests of Indigenous Child provisions.

To find out more about child protection and Indigenous families, see the resources Keeping Aboriginal Kids Safe and Parents’ Rights, Kids’ Rights on the Aboriginal Legal Aid in BC website.

Best interests of the child

Best interests of the childThe Family Law Act and the Divorce Act say that parents and the courts must only consider the best interests of the child when making decisions about children.

The best interests of the child include:

- your child’s health, safety, and emotional well-being;

- your child’s cultural identity, language, and heritage;

- your child’s views and preferences;

- the love and affection between your child and other important people in their life;

- your child’s needs, including the need for stability at their age and stage of development;

- who looked after the child in the past and how well they looked after the child;

- the ability of parents or others who want guardianship, parenting time, parental responsibilities, decision-making responsibility, or contact to care for and meet your child’s needs;

- whether any arrangements that require you and the other parent to communicate and cooperate are appropriate;

- whether there’s any family violence, and if so, the effect on your child’s safety, security, and well-being; and,

- whether there are any court proceedings or orders relevant to the child’s safety, security, or well-being.

Always think about the best interests of your child when making decisions about them. If you can’t agree with the other parent about what’s best for your child, you can get help from a mediator to work out your disagreement outside of court. If you still can’t agree, you can go to court and ask a judge to decide.

Possible parenting arrangements

After you separate, you and the other parent can plan how to continue caring for your child. You can make an agreement about parenting arrangements.

Here are some examples of possible parenting arrangements:

- The child lives with one parent most of the time, and this parent is responsible for making most decisions.

- The child lives with one parent more of the time, and the parents make decisions jointly.

- The child lives with each parent at least 40 percent of the time, and the parents make decisions jointly.

- One or more of the children live with each parent, and the parents divide decisions between them.

Moving with a child

After separation, you might plan to move — with or without your child. A move that has a significant effect on your child’s relationship with a guardian, a person who has parenting time and decision-making responsibilities, or a person with contact, is called relocation.

If there’s a parenting or contact order or agreement in place, check to see if it talks about relocation.

If you want to relocate, you need to take certain steps. What you need to do depends on which law you use.

- Under the Family Law Act, generally, if you’re a child’s guardian and you plan to relocate, with or without your child, you must give notice of your move to any other guardians and any person who has contact with the child. This means you must tell them where you plan to move and when, in writing, at least 60 days before you plan to move.

- Under the Divorce Act, if you have parenting time or decision-making responsibility and plan to relocate, you must give at least 60 days’ written notice to anyone else who has parenting time, decision-making responsibility, or contact under a contact order. The notice must say when and where you plan to move and must also include your contact information. It must also include a proposal for new parenting arrangements or contact if the move happens.

If you have contact with the child, and you’re planning to move, the Divorce Act says that you must notify people who have parenting time or decision-making responsibility of your plan to move. You must give notice in writing, set out where and when you plan to move (as well as your contact information), and provide a plan for new contact arrangements. You must give notice at least 60 days before your planned move.

Under both laws, you can ask the court to excuse you from giving notice of a planned move if doing so would put you at risk of family violence.

Objecting to a relocation

- Under the Family Law Act, only a guardian can object to your plan to move after they get the notice. They can object by filing a court application for an order to stop the move within 30 days of receiving notice of the move.

- Under the Divorce Act, only someone who has parenting time or decision-making responsibility can object to your plan to move. They must object within 30 days of receiving notice of the move, using a special form or filing a court application for an order to stop the move.

If a guardian or a person with parenting time or decision-making responsibility objects to your move, they can ask for an order that says you can’t move. To decide whether you can move, the court looks at a number of factors, including:

- the reasons for your move,

- whether your move is likely to improve your child’s or your quality of life,

- whether you gave proper notice of your plan to move,

- whether you suggested reasonable arrangements to protect the child’s relationship with the person who isn’t moving, and

- whether the move is in the best interests of the child.

A person who only has contact with a child can’t object. Instead, a person with contact can apply anytime for an order to change their contact time.

The Family Law Act and the Divorce Act both say you must try hard to work out your disagreements. To avoid an urgent and difficult court hearing (whether or not you have a parenting agreement or order), try to discuss your move with the other person before you make firm plans. Also, get a lawyer’s advice about how likely it is that a court would allow the move. Use mediation to help sort out new parenting arrangements or a new contact schedule.

See Help to make an agreement for where to find a mediator.

Concerns about parenting time or contact

Conditions in your court order

If you have concerns about the other parent or another person spending time with your child, you can ask a judge to include conditions in your court order to help protect your child. For example, the order could say the other person:

- can’t take your child out of the province,

- can’t use alcohol or drugs immediately before and during visits, and/or

- can only visit your child when a supervisor (neutral person) is there.

If you’re afraid for your safety or your child’s safety when they spend time with the parent or person with contact, see a lawyer immediately. If you can’t afford a lawyer, you might be able to get legal aid. You might also be able to get legal aid if the other parent has denied your parenting time or contact.

See Help from a lawyer for more about Legal Aid BC.

Denying parenting time or contact

The courts want to ensure children have meaningful relationships with each parent.

To deny parenting time or contact, you must have strong reasons showing that time with the other parent would be emotionally or physically unsafe for the child. Some examples include:

- you’re afraid for your child’s safety because of family violence;

- you believe the other parent was drunk or high when they were to have time with your child;

- over the past year, the other parent often missed their parenting time, or was late and didn’t give you reasonable notice;

- your child is ill, and you have a doctor’s note.

One parent can’t deny the other parenting time or contact because they don’t pay child support or are behind on payments. There are other ways to enforce non-payment of support.

Disputes

If you have a Family Law Act court order or agreement that gives you parenting time or contact and the other parent or guardian won’t let you see your child, try to sort things out with the other person outside of court. This can include getting help from a family justice counsellor or another mediator. If you can’t work things out, you can ask a court to enforce the order or agreement.

If the court finds the other parent or guardian “wrongfully” kept you from spending time with your child, the court can make an order that:

- you and the other parent or guardian must attend mediation or another form of family dispute resolution;

- you, the other parent or guardian, or your child must attend counselling;

- you can make up the lost time with your child over a period of time set out in the order;

- the other parent or guardian must pay you back any relevant expenses you incurred when you were denied time with your child;

- the transfer of your child from the other parent or guardian to you must be supervised;

- the other parent or guardian must pay you or your child up to $5,000 for denying you time with your child; or

- the other parent or guardian has to pay a court fine of up to $5,000.

If a person with parenting time or contact repeatedly fails to use their parenting time or contact with the child, the court can also make similar kinds of orders about that.

Child support

Child supportAfter they separate, one parent usually has to give the other parent money to help support the children. This is called child support. Parents, guardians, and sometimes step-parents have a legal duty to support their children, even if they don’t see or take care of them. The child support laws are based on the idea that children should continue to benefit from the ability of both parents to support them.

Child support is the child’s legal right, even though it is money paid to their parent or guardian. This means that a parent can’t “bargain away” child support. The court usually won’t accept an agreement that says one parent doesn’t have to pay child support in exchange for something else.

The parent who the child lives with most of the time is entitled to get child support from the parent the child doesn’t live with (called the payor). This is to help with the costs of raising the child. If the child spends the same or almost the same amount of time with each parent, the parent with the higher income usually has to pay child support to the other parent.

A parent can’t stop the other parent from having parenting time or contact because they haven’t paid or have fallen behind on child support payments. Child support and time with the child are separate family law issues.

Child support amount

The amount of child support that must be paid in BC is based on the Federal Child Support Guidelines (the guidelines), which are made up of a set of rules and tables. Courts use the guidelines and the tables to set child support.

To calculate the child support amount you can expect in your situation, you can look up the Child Support Tables. Go to the Department of Justice Canada website. Click Family Law and then scroll to choose Child Support. On that page, click the link to “Look up child support amounts.”

Support amounts are based on how much gross income the payor earns in a year and how many children you have together. The support amounts are different for each province. Like the courts, you would use the guideline tables for the province where the payor lives and works, even if the children live in another province.

To use the child support tables, you need the payor’s financial information. (If you have a shared or split parenting arrangement, both parents’ incomes are needed to calculate the support.) It’s important that you both honestly share all the up-to-date information you’d need if you went to court. If one of you doesn’t and the other parent finds out that what you provided to them was not true, incomplete, or inaccurate, they could go to court to have the support amount changed.

If you apply for child support in court, the person asked to pay has to provide you with a completed financial statement and attach tax returns and notices of assessment and reassessment for the past three years.

| If they’re | they also need to provide |

| an employee | their most recent statement of earnings |

| receiving Employment Insurance/EI | their three most recent benefit statements |

| receiving social assistance | a statement confirming the amount they receive |

If a person who has to provide financial information doesn’t do so, a court might estimate what their income is. This is called imputing income. The payor would have to pay child support based on that imputed income amount.

For Indigenous families

If the payor is a Status Indian who lives and works on reserve and doesn’t have to pay provincial or federal income tax, the courts adjust the Federal Child Support Guidelines income amount upward. The child gets more support because the payor’s income is untaxed. This adjustment is called grossing up income. It’s very important to know for sure whether the payor gets non-taxable income.

For Indigenous families, the courts also look at the financial help a child gets from their Nation for education expenses when they decide how much child support the parent or guardian must pay for the child.

If you have questions about child support, talk to a lawyer. See Help from a lawyer for where to find a lawyer.

Special or extraordinary expenses

The Federal Child Support Guidelines tables contain the basic amounts for child support (for food, shelter, and clothing). Most parents share an amount on top of basic child support for special and extraordinary expenses. These are extra expenses that are:

- necessary, because they’re in the child’s best interests (for example, if your child has a special talent), and

- reasonable, based on the family’s financial situation and whether the cost is affordable

Special expenses include:

- child care expenses;

- the portion of your medical and dental insurance premiums that provides coverage for your child;

- your child’s health care needs if the cost isn’t covered by insurance (for example, orthodontics, counselling, speech therapy, medication, or eye care, such as glasses); and

- post-secondary education expenses.

Extraordinary expenses include:

- extracurricular activities, and

- educational expenses other than post-secondary education (such as private school).

Usually, both parents contribute to the cost of special and extraordinary expenses in proportion to their gross annual incomes.

These expenses can be set out in an agreement or court order.

Undue hardship

If you think you won’t have enough money to support yourself after you pay child support, you can ask to pay a different amount. You can claim you’ll suffer undue hardship because paying the required amount of child support would make your household’s standard of living lower than the recipient’s.

If you’re the payor, you have to prove that the payments would be “undue” or exceptional, excessive, or disproportionate. Some examples of situations that can cause undue hardship include having:

- an unusual or excessive amount of debt

- to make support payments for children from another family (for example, from a previous marriage)

- to support a disabled or ill person

- to spend a lot of money to visit the children (for example, airfare to another city)

You can also claim undue hardship if you receive child support payments and you think the amount in the Federal Child Support Guidelines table isn’t enough to support your child.

In either case, you can ask the court to change the child support amount. Talk to a lawyer to find out if the court might consider your situation to be undue hardship.

How long child support lasts

Child support is usually payable for children:

- under age 19, and

- 19 or older if they can’t support themselves because of illness, disability, or some other reason, including going to school full-time.

How to change a child support agreement or order

If you have a child support agreement, you can change it at any time by making a new one if you and the other person both agree.

If the other person doesn’t agree with a change you want to make, you can apply to court to set aside (cancel) all or part of the agreement. The court might:

- replace the unfair provisions with a court order

- set aside your agreement if it’s different from what the court would have ordered under the law.

The Child Support Guidelines and court rules say that parents should exchange financial information every year. The amount of child support to be paid might increase or decrease based on that. If you and the other parent can’t agree, you can try mediation. If you can’t agree, you can go to court to ask for a court order.

If there’s a court order in place, either parent can make a court application to apply to lower or raise child support payments if there’s a change in circumstances, such as:

- a long-term income change for the payor,

- a change to a child’s special or extraordinary expenses, or

- a change in a child’s living arrangements or contact (such as where the child moves to live with the other parent, or divides their time between parents differently).

The court can also change the order if:

- circumstances have changed so much that a court would make a different order now,

- one person didn’t provide all the necessary financial information when the order was made, or

- important new information wasn’t available when the order was made.

The Supreme Court Family Rules , the Provincial Court (Family) Rules , and the Federal Child Support Guidelines all say when a payor and a recipient need to give financial information to each other.

Child support and income tax

Money paid under child support orders made since May 1, 1997, isn’t considered taxable income for the recipient or a tax deduction for the payor. Orders made before May 1, 1997, still have tax consequences.

See the Canada Revenue Agency website for details and search for “support payments.”

BC Family Maintenance Agency

Once you have an agreement filed at the court registry or you have an order for child support, you can enroll it with the BC Family Maintenance Agency or BCFMA, (formerly know as the BC Family Maintenance Enforcement Program, or FMEP). The BCFMA is a free BC government program that helps monitor and collect any support owed to you. You don’t have to wait until the payments are late to register. You can register the order or agreement immediately after it’s made. Sometimes it’s easier to have a third party to keep track of payments, and to receive and send them.

See Other free legal services for BCFMA contact information.

Settling Other Money Matters

Settling Other Money MattersUnless we say otherwise, the legal rights described in this section apply to people who are married or who live common-law for at least two years.

Spousal support

Depending on your circumstances, you or your spouse (married or unmarried) might have to contribute to the other person’s financial support after your relationship ends. Spousal support is partly intended to:

- compensate (make up) for any financial advantages or disadvantages either or both spouses might have because of the relationship or the separation, and

- help each spouse become financially independent within a reasonable period of time after separating.

If you and your spouse can’t agree on whether one of you should pay spousal support or how much you should pay or for how long, try to sort things out with the help of a mediator or another dispute resolution professional. If you can’t agree, you can go to court to ask for a court order.

See Final order.

If you apply for spousal support, the court looks at the following:

- how long you and your spouse lived together,

- if you stay or stayed at home most of the time with the children,

- if you worked outside the home during the marriage or relationship,

- if you can support yourself,

- whether you earn a lot less than your spouse, and

- if your spouse is able to pay.

If you were married, you must apply for spousal support under the Family Law Act no later than two years after you get a divorce order or annulment. If you lived together and weren’t married, you must apply within two years of the date you separated. There is no time limit for a married spouse to apply for spousal support under the Divorce Act.

Spousal support amount

If you must pay spousal support, the Spousal Support Advisory Guidelines can help you figure out the amount of support you should pay. Lawyers, dispute resolution professionals, and judges all use these guidelines to help them make a decision. The guidelines take into account:

- how much each of you earn and the sources of your income,

- how long you were together,

- your ages, and

- whether you have children.

For Indigenous spouses, if the spousal support payor is a Status Indian who lives and works on reserve and doesn’t have to pay provincial or federal income taxes, the courts adjust their income amount upward. This adjustment is called grossing up income.

It’s very important to know for sure whether the payor gets non-taxable income.

The MySupportCalculator website has a calculator that can give you a good idea of how much spousal support should be paid. You have to enter information about both spouses.

If both spousal support and child support must be paid, you need to calculate each of those amounts. Calculations are complicated, especially if you have children. You can see a lawyer to get a more accurate calculation of the payment amounts.

How long spousal support lasts

A spousal support agreement or court order can be for a specific period, or might not have an end date. If it’s for a set period, how long support is paid depends on many things, including:

- the length of your relationship,

- your roles in the relationship,

- your and your spouse’s ability to become self-sufficient, and

- each of your standards of living.

If your agreement or order doesn’t have an end date, it can set out circumstances when support ends; for example, retirement. Your agreement or order can also say you must review the spousal support after a set period. It can be helpful to review your circumstances regularly.

You might need to extend spousal support. You can change support more easily while the agreement or order is in place than after it has ended. If your order or agreement doesn’t say it has to be reviewed after a set period, it’s a good idea to apply for an extension before the agreement or court order ends. It’s also a good idea to get help from a lawyer.

BC Family Maintenance Agency

Once you have an agreement filed at the court registry or an order for spousal support, you can enroll it with the BC Family Maintenance Agency (BCFMA), formerly known as the BC Family Maintenance Enforcement Program (FMEP).

The BCFMA is a free BC government program that helps you collect any support owed to you. You don’t have to wait until the payments are late to register. You can register the order or agreement immediately after it’s made.

See Other free legal services for BCFMA contact information.

Changing the spousal support amount

You can apply to set aside (cancel) a spousal support agreement if the agreement is unfair or was made unfairly. For example, if one spouse:

- provided inaccurate financial information or withheld important information,

- took advantage of the other spouse, or

- didn’t understand the agreement.

The court might also set aside an agreement and replace it with a court order if the agreement is “significantly unfair.” To figure out if the agreement is unfair, the court would look at:

- the length of time since the agreement was made,

- any changes in either of your circumstances,

- whether (and to what extent) you both intended this agreement to be final,

- how much you both rely on the current agreement, and

- whether the agreement meets the Family Law Act spousal support goals.

You can apply to change a spousal support order when a significant change happens in the “condition, means, needs, or other circumstances of either spouse.” These changes could include the following circumstances:

- The payor becomes unemployed or disabled and can’t pay.

- One of the spouses lives with someone else or remarries, so their expenses decrease.

- One of the spouses gets a financial windfall, like a lottery win.

Property and debt

The Family Law Act sets out the law for how property and debt are divided after a couple separates. In most situations, the law is the same for married spouses and unmarried spouses living together for at least two years. The information here explains when the rule is different for unmarried spouses.

How to divide family property and debt

Unless you have a written and signed agreement that says otherwise, the law assumes all family property and family debt will be divided equally. This applies unless it would be “significantly unfair” to divide it equally.

It isn’t easy to convince a court that an equal division would be significantly unfair. To decide if it would be, the court looks at many factors, including:

- how long the relationship lasted,

- if both spouses made any agreements other than written and signed ones,

- how much each spouse contributed to the other’s career or career potential,

- how the family got into debt,

- each spouse’s ability to pay a share of family debt if one spouse’s debt is more than the family property is worth, and

- if one spouse did something to raise or lower the family debt or property value after the separation.

If you were married, you must apply to BC Supreme Court to divide family property or debt no later than two years after you got an order for divorce or annulment.

If you were unmarried, you must apply to BC Supreme Court within two years of the date you separated.

It’s best not to agree to get a divorce until you deal with property division issues.

Family property

Family property is everything either you or your spouse own together or separately on the date you separate. This includes:

- the family home,

- RRSPs,

- investments,

- bank accounts,

- insurance policies,

- pensions,

- an interest in a business,

- the amount that pre-relationship property (property owned by one spouse before the relationship started) increased in value since the relationship started, and

- companion animals.

Companion animals (pets)

Family property also includes companion animals (pets). As of January 15, 2024, the Family Law Act states that separating or divorcing spouses can make their own agreement about the possession and ownership of pets. The agreement may include that the spouses:

- jointly own a pet,

- share possession of a pet, or

- give exclusive ownership or possession of a pet to one of the spouses.

For more information about reaching agreement, see the BC Government website.

If you and your spouse can’t agree on who gets the family pet, one of you can apply to BC Provincial Court or Supreme Court for an order. The court will consider various factors and make a decision about which spouse gets ownership and possession of the pet. (The court can’t declare that spouses jointly own the pet or require spouses to share possession of the pet.)

People who aren’t spouses may be able to resolve a pet dispute by agreement or by going to the Civil Resolution Tribunal, BC Small Claims Court, or BC Supreme Court, depending on the value of the claim.

It doesn’t matter whose name the property is in.

Excluded property (not family property)

Not all property that each of you have is family property. You and your spouse can take some things out of the marriage without having to share them. These exceptions to family property are called excluded property. This includes:

- property that one spouse owned before the relationship started, and

- gifts and inheritances given to one spouse during the relationship.

If excluded property increases in value during your relationship, the increase is considered family property. For example, say your spouse owned a house when you started living together. You aren’t entitled to an equal share of the house’s total value. But you’re entitled to half of the increase in the house’s value since you started living together.

Also, excluded property remains excluded property, even if you put it into joint names. For example, say one spouse inherits $100,000 and uses it to buy property in joint names with their spouse. Under the Family Law Act, the $100,000 stays excluded property after separation as it can be traced back to the spouse who contributed it. But a court can decide to divide excluded property in certain circumstances if a claim is made.

The law in this area changes and can be complicated. Get legal advice if you can. For information about this area of law, see the Family Law in BC website.

Property division for Indigenous people with non-Indigenous spouses

Information in this section applies to:

- Status Indians, and

- non-Indigenous people who have children with Status Indians.

For financial assets, like cash, bank accounts, stocks, and bonds, the same personal property division laws apply to Indigenous and non-Indigenous spouses. This is because financial assets are kept off reserve.

Homes on reserve for Indigenous and non-Indigenous spouses

The Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act (FHRMIRA), in place since December 2014, means if you live on reserve, you’re protected:

- during your relationship,

- if you and your spouse or common-law partner separate, and

- if your spouse or common-law partner dies.

The FHRMIRA applies to married and common-law couples living on reserve, if at least one person is a First Nation member or a Status Indian. It applies to opposite-sex couples and same-sex couples. The Indian Act says common-law means living together in a marriage-like relationship for at least one year.

The FHRMIRA intends to give the same rights and protections to the family home that people who live off reserve have. It gives people who live on reserves protections and rights until a First Nation community makes its own matrimonial real property laws under the Act or other legislation.

What matrimonial real property means

Under the FHRMIRA, matrimonial real property means houses, land, and structures a family uses. You might have got this real property before or during your relationship. The act doesn’t include other property you use for a family purpose, such as cars, money, and household furniture.

Matrimonial real property doesn’t include gifts you got in a will, or when someone died without a will, or real property you bought with money from those gifts.

When a relationship ends

Under FHRMIRA, when a relationship ended and only one spouse or common-law partner had a certificate of possession, the other person might have had to leave the family home. The courts could only make orders for families on reserve to divide the value of matrimonial property (house, cash, cars, etc.).

Under the Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act, the courts can make orders about the home. These include who can live in it and for how long, how matrimonial property is divided, and other protections about the home. This means the court can:

- remove violent partners from the family home, and

- apply a First Nation’s own matrimonial property laws when they exist.

This means that even if you aren’t a First Nation member, and even if your children aren’t First Nation members, you and your children might be able to stay in your home on reserve.

If you or your spouse or common-law partner want to decide what to do with your family home on reserve after you separate, the law says:

- you must first get the “free and informed” consent of your spouse or common-law partner, and

- you must get their consent in writing.

First Nations laws

First Nations can make their own matrimonial real property laws. Or they can follow the FHRMIRA until they make their own laws.

The act doesn’t cover:

- First Nations who have their own matrimonial real property laws (you can ask the Nation if they have their own laws),

- First Nations with a self-government agreement (unless they have reserve land and choose to follow the act), and

- First Nations with land codes in place under the First Nations Land Management Act.

Family debt

Family debt includes all debts that either spouse took on during the relationship. This might include:

- mortgages,

- loans from family members,

- bank lines of credit or overdrafts,

- credit card payments, and

- income tax.

Family debt also includes debts taken on after spouses separate if the money was spent to take care of family property.

It doesn’t matter whose name the debt is in.

Both spouses are equally responsible for family debt. The court orders an unequal sharing of debts only if it’s “significantly unfair” to divide it equally.

However, creditors can demand payment only from the spouse who took on the debt. If a couple has joint debts, creditors might choose to demand payment from only one spouse.

You might want to do the following when you separate:

- Tell all your creditors in writing you’re no longer with your spouse. Keep a copy of your written notices.

- Cancel any joint and secondary credit cards.

- Talk to your bank about any joint accounts you have.

- Reduce the limits on overdrafts and credit lines to what you owe now. Or see if you can change the account so that two signatures are needed to withdraw money.

- If you need credit, ask the bank to open a line of credit in your name only.

- Think about changing the beneficiary of your investments, RRSPs, insurance, and will to someone else, such as your children, if your spouse is the beneficiary.

This can get complicated. You might need to get some legal advice. See Help from a lawyer to find one.

Benefits

If you and your spouse separate, you also have to think about what to do about the benefits you get through your work.

Extended medical/dental plans

If one spouse’s extended medical plan provides coverage for the whole family, you need to find out the rules for separated or divorced spouses. Usually, the plan continues to cover the children.

If the plan covers a separated or divorced spouse, your agreement or order should say the coverage continues. If the plan doesn’t cover a separated or divorced spouse, you have to apply for separate coverage.

Financial help

If you don’t have enough money to live on, here are some options for getting financial help.

Welfare

Welfare is money and other benefits the BC government gives to people who don’t have an income (usually wages or a salary). There are rules about who can get these benefits.

If you’re already on welfare, tell the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (the ministry) you separated from your spouse. This affects how much welfare you get each month.

See How to Apply for Welfare, Welfare Benefits, and When You’re on Welfare.

If your children live with you and there isn’t a child support agreement or order in place, the ministry might arrange for you to meet with a family maintenance worker to talk about getting child support from the other parent. The ministry might try to arrange for a child support agreement or court application to get an order for child support from the other parent. If you don’t want the ministry’s help to apply for support, you can tell them that.

Seniors’ benefits

Spouses who were married or lived together in a marriage-like relationship for at least one year are entitled to federal benefits such as the Old Age Security (OAS) pension, the spouse’s Allowance, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS).

The spouse’s Allowance is for couples with low incomes. It’s paid to spouses who are 60 to 64 years old if their spouse is 65 and getting an OAS pension. If you’re getting the spouse’s Allowance, and you’re between 60 and 64 when you separate from your spouse, your Allowance stops three months after you separate.

GIS is based on your and your spouse’s combined income. If you separate and are living on a low income, you might qualify for GIS as a single person. Let the GIS office know right away that you separated from your spouse.

Canada Pension Plan credit splitting

When a relationship ends, the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) pension contributions a couple made while they lived together can be shared equally between them. This division is called credit splitting. You must ask to have your CPP credits split. To qualify, unmarried spouses must have lived together for at least one year.

If you are or were married, there’s no time limit to apply, unless your spouse dies. Then you must apply within 36 months of the date of death.

If you were living in a marriage-like relationship for one year, you can apply for credit splitting after you live apart for 12 consecutive months. You must apply within four years of the date you began living apart.

If you signed an agreement with your spouse or partner that says you won’t split CPP pension credits, you usually have to stick to that agreement.

For more information, see the online booklets When I’m 64 on the People’s Law School website. Or contact Department of Employment and Social Development Canada.

1-800-277-9914 (English)

1-800-277-9915 (French)

1-800-255-4786 (TTY)

Taking care of other details

Separation or divorce doesn’t automatically change your banking or beneficiary information. If you separate from your spouse, you might want to take the actions listed in the Family debt section above.

Also let the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) know you’re separated after you’ve been apart for at least 90 days. In some cases, you might qualify for extra Canada child benefit or GST credit payments.

To change your marital status, call CRA at 1-800-387-1193 (press 1 for the Canada child benefit, then press 1 to speak to a representative). Or fill out a Marital Status Change form and send it to the tax centre in your area. For more information and to get the form, see the Government of Canada website . In the search bar, type marital status change. Click the link to open the page.

Get legal advice to protect your finances and credit, and to learn about your options. You especially need legal advice if you own a house, car, or other property (like joint bank accounts) with your spouse.

See Help from a lawyer for how to find one.

If You Can’t Agree — Going to Court

If You Can’t Agree — Going to CourtIf you and your spouse can’t agree, either of you can ask the court to decide how to resolve some or all of your family law issues in a court order.

But you might be able to settle some or all of your issues without a court hearing. The following options will help you settle as much of your case as possible without a court hearing.

Going to Provincial Court

The Provincial (Family) Court has rules about which registry you can use.

Provincial (Family) Court registries offer extra, free services to help people resolve their family law issues without going to court. Depending on your registry, you have to use the services it offers before you can file an application with the court.

For more information, see Provincial Court Registries (go to family.legalaid.bc.ca and search “Provincial Court Registries”).

Exchange information

The law says you and your spouse must provide each other with “full and true information” so you can resolve your family law dispute. This rule applies whether or not you go to court.

The court rules also set out exactly what information you must provide before you go to court. If you refuse to provide this information, the court can make various orders, including:

- requiring you to provide the missing information and documents, and

- ordering you to pay a fine or to pay the other person’s legal costs.

Meet with a child support officer

Child support officers can help you understand the child support guidelines and calculate how much child support you should pay or get. Child support officers are available at Family Justice Centres in Kelowna, Nanaimo, Surrey, Vancouver, and Victoria.